Title: Party of a Lifetime

Artist: Paula Flores

Year: 2022

Exhibited at: Kunstraum Feller

Description

With sunlight and moonbeams…

Party of a lifetime

Text by: Lorena Tabares Salamanca

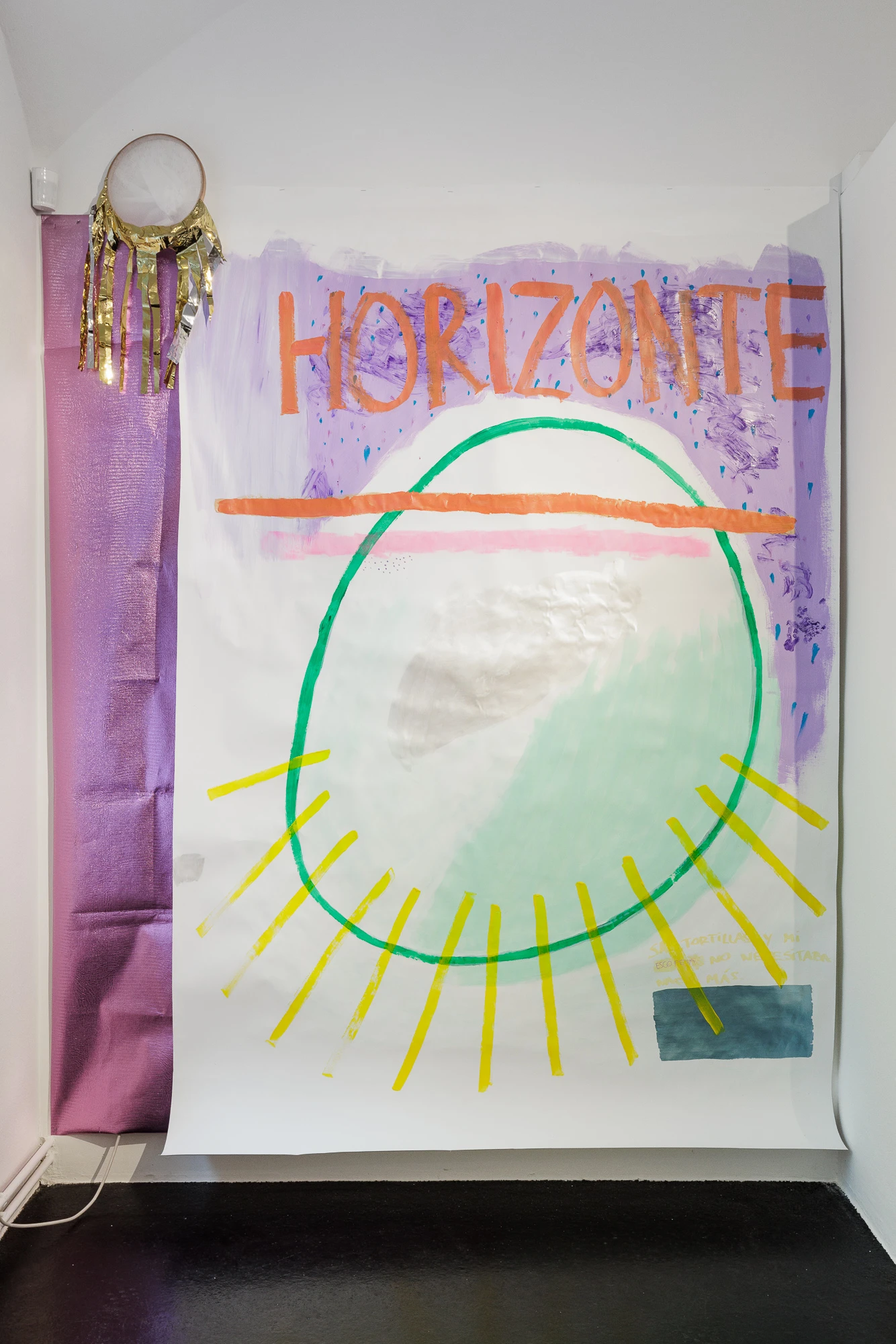

The ‘telepathic’ desire of Paula Flores branches out in this exhibition and creates an orbit of gestures that transport us to Mexico: the analogies between the hyphae of mycelium, the emotional networks and the hallucinatory experiences permeate the gallery in Vienna. In this pictorial-sensorial space, curated by Marcello Farabegoli, integrates in its two rooms the installation Party of a lifetime (2022) and another group of works that complement each other to transport us to a desert of varied shades with colourful splashes of wild grasses, branches and plants, in which natural and artificial artefacts coexist organically deployed throughout the place like vestiges of multiple dimensions of a space but also of time.

Living in Austria for several years has implied for Flores a profound path of longing. The more time and distance we keep from the triggers in our memory, the more we lose it into a blur like stupor. This affective dispute against time is transferred to a field of ‘fertile images’ where we observe self-generative forms of birth, rituals, celebrations, and certain intimate and familiar passages of life emotionally chosen by the artist in her wanderings through remembrance. The fertility of the image becomes apparent through the production of that to which it refers: the altar corresponds to the ritual, a detonating representation appeals to memory, crops harbour corn seeds in a periodic germination, and so on. With this in mind, a possible vector that runs through this imagery can be thought of as follows: firstly, in the lunar calendar with this celestial body at the centre of the mountain as a sign of fertility (Moons of you, 2022); secondly, in the growth of the wild plants sown in the natural fabric that envelops Flores’ sleeping and heartbeating body (Quelites, 2019-2022) or in the container space (Party of a lifetime) of the images that rewrite Flores’ past with her grandfather interweaved with organic materials such as wool, curcuma and corn kernels; finally, at the centre of the room there’s a circular altar in golden mirror-like plastic which suggests us the following orientation proposed in this space. Where does this unusual compass lead us?

The creation of altars with their respective offerings like seeds, coloured papers and affective objects in memory of a deceased person or as a commemoration of the harvest is a common cultural manifestation throughout Mexico. In particular, its current configuration incorporates indigenous but also Catholic elements at different levels. An unequal cultural hybridism. From another perspective, in many of the country’s mestizo and indigenous societies, the ‘hybrid’ altar implicitly accounts for the process of colonization initiated five hundred years ago by the Spanish Empire. This process of cultural collision bounded indigenous ritual elements and behaviour to transform in order to survive, which is why the vertical arrangements are associated with religious altars in Catholic chapels, and why the celebration of the Day of the Dead on the 2nd of November corresponds to the day of the blessed souls and the faithful departed. While Flores focuses on altars as collective social manifestations, she shifts her interest to a temporality other than that of the Gregorian calendar, which is driven by Catholicism.

In her own altar the artist refers to the ceremonies of contemporary Mayan culture. These indigenous communities that nowadays inhabit mainly the south of Mexico, Belize, El Salvador and Guatemala elaborate altars with food, plants and volcanic stones placed directly on the ground sometimes with the addition of candles and often also incorporating wooden structures, but always in a horizontal approach. This accommodation forces the body to connect with the energy of sowing and growing in an experience different from altars with upward and vertical orientations. In these events, the Aj’qij, the Mayan priest, also known as the Counter of Time, guides the ceremony according to the Nahual or vital energy that corresponds to that exact day in the Mayan calendar. This instrument has twenty Nahuales or figures that govern the thirteen months of the year and its two hundred and sixty days. Its formulations of time are cyclical and constitute a neverending renovation of time(s) and becomings.

One of the main critical points of this exhibition lies in its approach to temporal dimensions; the simultaneous existence of multiple models of time is part of the indigenous resistances against the colonial model. If we recall the worldwide delirium that brought about the, so called, end of the Mayan calendar, we can observe how the desire for possession of cyclical times created a fictional disaster rather than a real understanding of the epistemological complexities of societies that are both ancestral and contemporary, such as the Maya. In 2012, apocalyptic news linked to a supposed end of the world went viral; this was a result of the unilateral interpretation to ancestral traditions whilst the linear time of capital continued its, seemingly, unstoppable progression. Such an event contains many paradoxes, such as the purposeful dissolution of the value system of a culture in order to make way for economic speculation. According to the Brazilian indigenous philosopher Ailton Krenak (2021), the idea that the world is coming to an end is an excellent excuse for doing nothing. Social inertia, in which peoples and species are left in the past, is a convenient way to manipulate collective existence towards the elimination of what the Maya themselves call being part of ‘other worlds’. Additionally, Flores makes of a gesture, of a singular altar, a current formulation of the alchemy of value: the golden plastic or the remembrance of gold is a mirage through which the ritual and symbolic value of this mineral has become part of a model of production and a currency with merely speculative potential. Is there any room left in us to reinvent the value of life in any other way than solely through transactional value? In the altars, the value of what is intimately affective is made visible yet the elements placed there don’t actually escape the world of the prices.

The artist’s invocation of these invisible and remote connections with Mexico, under the effect of the imagery, challenges the Eurocentric paradigm that pigeonholes into terms such as “illusion” and “superstition” everything that goes beyond the rational and linear understanding of the world. The US-American geologist, Stephen Jay Gould, argues that linearity embodies the deepest Western meanings and thoughts about the essence of time (1992, p. 19). In other way, ‘The Arrow of Time’, as Gould refers to this crescent line effect, constitutes the engine of progress, development, modernity and all its, constructed, negative counterparts. In a broadened spectrum over the history between Europe and America, the ways of life radically different from this paradigm were imbued in the whirlwind of modernity, initiated by the European navigations of the sixteenth century. Nowadays, also the modern system of coloniality reinforces this model of dissolving globalisation and violently continues it with the dominance of capital.

Throughout Mexico, the social and economic outcome of this is evident. For example, in Tijuana, where Flores was born and raised, regional urban development was driven by the demand for cheap labour from the United States. In short, the border position turned areas like this one into corridors for the transit of migrants but also of goods, becoming liminal zones for the the export of natural resources and minerals, and the import of all kinds of disposable gadgets or, as the curatorial group Los Yacuzis calls these, ‘underdeveloped chácharas’. It could be argued that the neoliberalisation of the country goes hand in hand with the disproportionate increase of “gaudy”, shiny and fluorescent polychrome artefacts and decorative elements. In fact, the growth of imported synthetic materials created a material and symbolic system in the country that permeated many of its cultural manifestations. In particular, children’s toys, piñatas, holiday garlands, religious amulets and reminders, and a long list of other objects. This recent stage of modernisation and industrialisation creates a rather interesting tension in Flores’ work: the attractive artificial appearance is mixed with the softness of the dyes dissolved in water together with the warm tones of the natural fibres and powders. The combination of this range of materials and colours reminds us, at times, of the gradations of light in the desert at sunset or the big cities with faded facades that join the vibrant nights; the urban monster that is Tijuana is growing and growing and has no time left to paint its face.

A chromatic mix in which the economy of colour intervenes is reproduced in the shine of metals, such as gold and silver, and precious stones. In reality, these are plastic fictions that decorate a party of which only the leftovers have remained. In the rooms of this Party of a lifetime, the pale and opaque tones of the sand becomes a background witness of the fragile existence of the Kumiai (Steps through the dry, 2022) which are the nomadic societies that once walked the territory with no borders other than those defined by their own feet. Today, a small group of their descendants live organised in small sedentary/nomadic nuclei in both sides of the modern imposed border with the U.S. (Los De La Baja / The Ones From Baja, 2022).

In the meantime, the day falls and the desert takes on different hues (Sun, 2022). As the light waves pass through the clouds of suspended sand, a collision with the atmosphere paints the sky pink, violet or coral. These tones, used repeatedly by Flores, are scientifically known as the ‘Rayleigh scattering’ effect. Around this phenomenon, the poetics of the sunset reveals itself in a spectrum of emotions such as nostalgia and longing, whether for the face-to-face encounter with her grandfather or for the festivities from her past.

Beyond cyclical, linear, and geological time, Party of a lifetime is a vehicle of hallucinogenic ramifications. This experience is revealed in a possible image of María Sabina’s first encounter with ‘healing consciousnesses’ (In a long blink, 2022) as well as in the mycelia scattered around the room (previously cultivated by the artist) or in the representations of different mushrooms scattered in the space (Closely, 2022). However, what is hallucinogenic is not only in the signs but also in the effect of reading the traces, the fibres and all the symbols. In the digital essay Telepatía colectiva 2.0: pequeña teoría de las multitudes interconectadas (2007), José Luis Brea argues that all writing possesses a load of content that requires a hallucinatory exercise. This suggests a relationship between writing as a telepathic channel and reading as a hallucinogenic procedure. In this way, the telepathic understanding of the pictorial projection turns the painting into a vision machine through which the artist’s faintest memories circulate.

Consequently, we suddenly share Flores’ imaginative desire to give a place to remembrance experiences but to actualise them with a new network of messengers (us). Hence, hallucination and telepathy are indiscernible from her desire to travel through simultaneity, from Vienna to Tijuana. In a similar line with this discernment, authors such as Brea (2007) declare that: “The question of telepathy has to do with two things: first, how meaning appears as a ghost there where it is not – or how that which does not speak speaks – and, second, what is its temporality. Or to put it another way: whether in telepathy there really is simultaneity, synchrony between distants, or perhaps anticipation”. Although the announcement may seem late, it should be noted that the perspective of this text is thought from the past-present-future chained together and adjacent to the machines of science and technology. In this sense, the ‘spectrality’ that characterises all projections of time, has a speed that is impossible to define. Memory as an ungraspable phenomenon rests relatively in those triggers of its appearance (in voices and images), without us really being able to capture it in a single element or story. The memory is in one and in many parts at the same time, that is why its spectrality is inherent to its appearance; the ghost comes to our call and without asking permission shows us ‘another self’ to that which we see from afar.

In addition to being a hallucinogenic vehicle, this exhibition acts as a container for references to the extra-sensory connections between human and non-human beings; the similarities between living beings surpass the idea of a closed and absolute unity called the human body. The ramifications of trees and fungi allow the circulation of information just as neural networks become channels through which thought and dreams travel. These networks, with different characteristics but similar in their function and morphology, intertwine in a metaphor about the indiscernible union of all beings as part of nature, in this sense, they unravel the Western dichotomy of the ‘natural’ object.

Finally, telepathy as simultaneity and anticipation (clairvoyance) leads us to other key and transversal aspects of Party of a lifetime: the colonialism of ancestral knowledge, the real power of mushrooms and the capitalisation of their mass consumption in a ‘globalised’ world. A paradox looms over the figure of the shaman María Sabina, on one side the appropriation of her knowledge without even referring to her or her culture, and on the other side the rejection of her by her own community for the unjustified use and subsequent abuse of the sacred. Thus, the relevance of mushrooms in recent decades emerges stripped of her figure as well as of the ritual, curative and collective relations stemming from Mazatec social practices in Oaxaca. Television and popular world turned this woman’s face into a mask under which ancestrality is confused with frivolity. The stripping of the visionary and communicative effects, which already happened in the 16th century on so many other cosmovisions or senses of the world, led to its resignification in psychedelic and recreational experiences that were massified in Hippism and pop culture in the United States, attracting to Mexico all kinds of curious people who ended up declaring themselves “experts” in these practices.

Postscript: ‘Ten, a hundred, a thousand times we will come back’. Legend has it that telepathy was never proven, although the Spanish colonisers of the 16th century were suspicious of the instantaneous nature of communication between indigenous societies. As they did not know the real reason for such immediacy of messages, they began to kill the messengers, the telepaths… This was, for example, the case with the Araucanians, and the Mayas.

Text by: Marcello Farabegoli

Paula Flores was born in 1988 in Tijuana / Mexico. She studied from 2010 to 2015 at the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California in Tijuana, where she received a bachelor’s degree in Plastic Arts. In 2018 she came to Vienna / Austria, where in 2021 she obtained a master’s degree in Art & Science at the University of Applied Arts Vienna. It is remarkable that, contrary to the mainstream in Mexico, Flores dedicated herself to abstract-gestural art at a very young age and thus faced strong headwinds at the Mexican university, which offered a classical-figurative education. Stylistically she was also influenced by the “Exvotos Mexicanos” (Mexican votive offerings are representations of popular art), the “Rótulos Mexicanos” (hand-painted commercial posters full of color and ingenuity in which images coexist with varied typographies), and both traditional indigenous and mestizo woven and embroidered textiles. She gradually began to explore the roots of her family – her grandparents, who had a close relationship with nature, play an essential role – her culture in general (festivities, rituals, etc.),

especially the precolonial ones, and her own relationship with nature. Along the way, she also encountered the world of shamanism, especially Maria Sabina (1894-1985), who revealed the miraculous power of entheogenic mushrooms (psilocybin) to the western world. So Flores began to study the mysterious world of mushrooms and other living beings like bacteria and some plants, topics that she then deepened at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. Thus she developed her own painterly style, a mix of abstract-gestural painting with figurative elements. These mostly have a symbolic intention and are deliberately naïve in character. Due to the joyful colorfulness the works in general appear Mexican or South American to Western eyes. At the same time, when you see for example her sculptures made of mycelia, some of her actions/performances, and videos, you also recognize another enigmatic side of the artist,

which cannot be pigeonholed into a particular subject, ethnic group, nation etc., one that is about deep questions about our existence, our relationship to nature and the universe.

In general, Paula Flores is concerned with the complexity of nature, with our knowledge or ignorance of it and our relationship to it. How is it possible, the artist wonders, that Western capitalist-imperialist thought, conceived predominantly by men, has enabled a part of humanity to legitimize the exploitation of enslaved and oppressed populations and groups of people, and nature no less?

Thus Flores seeks ways to change, dismantle, and overcome these hierarchical conceptual constructs that can limit us in the understanding that we may have of the natural interconnectedness of the world. To do so, she is studying “extraordinary ways of communication” between humans and other species, such as fungi, bacteria, and plants. In this context Flores is very interested in symbiogenesis: in the biological world the endosymbiotic theory is when two or more different organisms live in close physical contact – it brings together unlike individuals to make larger, more complex entities i.e. lichen. The artist hopes that symbiogenesis may lead to a shift in the balance of power and possibly pave the way for a more balanced relationship between humans and nature that would benefit the entire planet.

On the other hand, Flores is interested in the duality between life and death and questions where the sharp boundary between these states or concepts might be found. Regarding this fundamental contrast, it should be mentioned that the famous Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger, with his legendary essay “What is life?” published about eighty years ago, had pointed out the great riddles of the phenomenon of life as well as the associated principal explanatory hurdles, and at the same time had given an essential impulse to genetics. Remarkably, the current state of knowledge is still not sufficient to understand how life arose. Likewise, it is still technically impossible at present to create artificial life. Last but not least, a virus, i.e. a being which exists as such by definition between life and death, played a generally known frightening role in the Covid 19 pandemic.

On what seems another side of the spectrum, in so-called animistic religions, for example, a kind of soul is attributed to any natural object. Perhaps children today may still have the ability to feel this all-soul; some artists in particular often cultivate this ability throughout their lives. In her childhood, Flores herself was able to cherish a “magical feeling” concerning nature and recognized this particular effect even more intensely in the stories of her grandparents, who grew up in the countryside, whereas she grew up in Tijuana – one of the most active borders in the world. Flores’ will to find a way of transformation by means of explorative-artistic work, which is to break through the dual concept of life and death, to explore what is in between might seem particularly radical. She be – lieves that through this she can attain a connection to beings that animate the universe.

The exhibition at Kunstraum Feller from 5 November 2022 to 6 January 2023 that I curated in Vienna is divided into two rooms: one on the right with the installation “PARTY OF A LIFETIME” (2022) and one on the left with works mainly from 2022 that are closely related to this installation, as well as a few works from 2019 and 2020.

All the works in the left-hand room deal with very different themes, but are connected by a red thread.

One for example is an homage to the native people of Baja California, a state in Mexico and suggestive peninsula bordering the US states of California – Tijuana, where Flores grew up, is the biggest city in this state. Near to this work, you can find another that has to do with the feeling of space in the desert, a landscape closely associated with the artist. Mushrooms appear again and again in the works of Flores, who connects them to the moon and healing. In the works, elements can be found that have to do with ephemeral festivities, dances, rituals, velada5 and all kinds of celebrations. It is also about copal and salvia blanca, which in Mexico are used to cleanse “bad energies” or any other energies and have a similar status to incense in Europe, about healers and spiritual guides, and in general the search for one’s own paths or aberrations. In a larger landscape format, Flores shows how her grandfather taught people to remove ahuates (cactus thorns) from their hands and in a small portrait format Flores asks herself about the possibility of feelings of isolation of potted plants…

For curatorial reasons, three photographs from the performance “QUELITES” (2019) have been included in this more “classical” part of the exhibition. In this performance, Flores slept for several nights in a self-made wool blanket in which she had planted lettuce seeds and made them germinate thanks to her body heat and exhalations. At the same time, her skin also gradually came into direct contact with the fine roots of these plants. Especially in sleep, when our waking consciousness gives way to our subconscious and we confront our deepest fears and desires, Flores, as a life-giving being, tried to establish an intimate connection with the plants. It is about energía dadora de vida, she says, as it is called in the Temazcal6 ritual. The artist wonders what the energy of a newborn plant, growing skin to skin with us, can teach us: What can we give to this new being and what can we get from it?

Can we get in touch with the plant emotionally and feel the energy of life itself?

Last but not least, the video “IN A LANGUAGE WE DON’T UNDERSTAND” (2020) could also be seen in the room, in which according to the artist a “concoction of her existence that trespasses the understanding of aliveness, gathering of knowledge that doesn’t have a beginning or an end, learning by mirroring through and with others”.

The installation “PARTY OF A LIFETIME”, which consists of several paintings and sculptural components, is a tribute to the aspects of nature that Paula Flores grew up in, the stories that her grand-parents talked about, and the festivities from her home country that celebrate nature on its own and humans’ relationship with nature. The idea was born from the thoughts of Flores’ grandfather, who grew up in the rural area of Los Altos de Jalisco / Mexico. When he was only six years old due to family circumstances sometimes he wandered off alone into the mountains near his town. He took a kilo of tortillas with him and an escopeta (small rifle) which he hunted with. But he loved also to grab the fallen fruit from the ground that generous nature gave. He slept on the ground accompanied by the stars, which gave him plenty to think about, and enjoyed the freedom. On the other hand, it was Flores’s grandmother who talked about the magical aspects that were hidden within nature and the powerful connections to their ancestors, which must be kept alive by paying tribute, speaking to them, and having them always present in their lives and never stop being amazed by their wonders… the grandmother also taught her the festivities, from catholic/indigenous celebrations, rights of passage and tributes to secret playful spirits that lived in nature.

After several years of living in Vienna, the Mexican artist started to feel painfully distant from all of this, not just because of the physical distance, but because she had started to change. Even if, for example, nature in Austria is also beautiful, she cannot create this inner connection as in Mexico. And she also misses home because of the lack of festivities that are meaningful to her. According to the artist herself: “If we are not here to appreciate the beauty of life (birth), growing up, changing, energies we can’t see but can be interacted with and death then what are we here for? In these very diverse festivities from mestizo to indigenous practices, I find a mirror. A mirror that reflects how we relate to nature, how it is represented and intertwined in our daily life, scheduled festivities, spontaneous and sporadic rituals, parties, gatherings, veladas, etc… This is how we bring nature into our mind and into our soul. This is how we keep it alive.”

But now back to the installation itself: in Mexico, it is customary to stage parties, especially for children, on the basis of a particular theme, and this is what Flores has also done by sticking to the above-mentioned themes.

In general, the theme of imitation plays an important role in Mexico. At first glance, one notices several larger and colorful canvases attached to wooden poles and hanging airily and playfulness in the room. In between, various objects lie on the floor and the room itself is adorned with more or less glittering party decorations. A mysterious wallpaper door is slightly open and party paper scraps invite you to open it…

The rigid geometric structure of the room is organically broken, so that the artist manages to achieve the illusion of a cheerful, even childlike gaiety. One can perhaps even get the impression of having arrived at an Indio tent camp in the middle of nature and still feeling the dances of the inhabitants.

On the canvases, which are mostly made with acrylic paint, one can recognize elements that can also be seen in the paintings in the other room, such as mushrooms and plants. One also distinguishes stones, rivers, but also urban landscapes, and even a highway – where people dash back and forth in their cars, the artist says, and no longer even notice the surrounding nature. And at the same time, more elements from her grandfather’s stories appear, such as fig cacti, dragon fruit, and pomegranates one which he fed. Somewhere you also recognize his above-mentioned escopeta. There are also figures that appear to be somewhere between human and animal – these are the powerful shamans Nahuales, who according to tradition can actually transform themselves into animals. In one image, one shaman whispers secret knowledge to the other, while in the other they drink tea together as cow- or dog-like creatures. There are many symbols and references, such as to the Mayan codices, which were initially perceived as primitive by the Western world because of their otherness. But nevertheless, not everything can be explained and there is a lot of mystery. The artist no longer knows why she painted a menacing centipede, for example, and that is a good thing, because the works were created intuitively and as if in a dream. This is also one reason why Flores did not take the path of strictly figurative painting, in order to preserve this special freedom. She believes that this also allows her to access the emotional world, both her own and that of the viewer.

One of her works, for example, is completely abstract and, with violet-greenish colors, merely alludes to the water

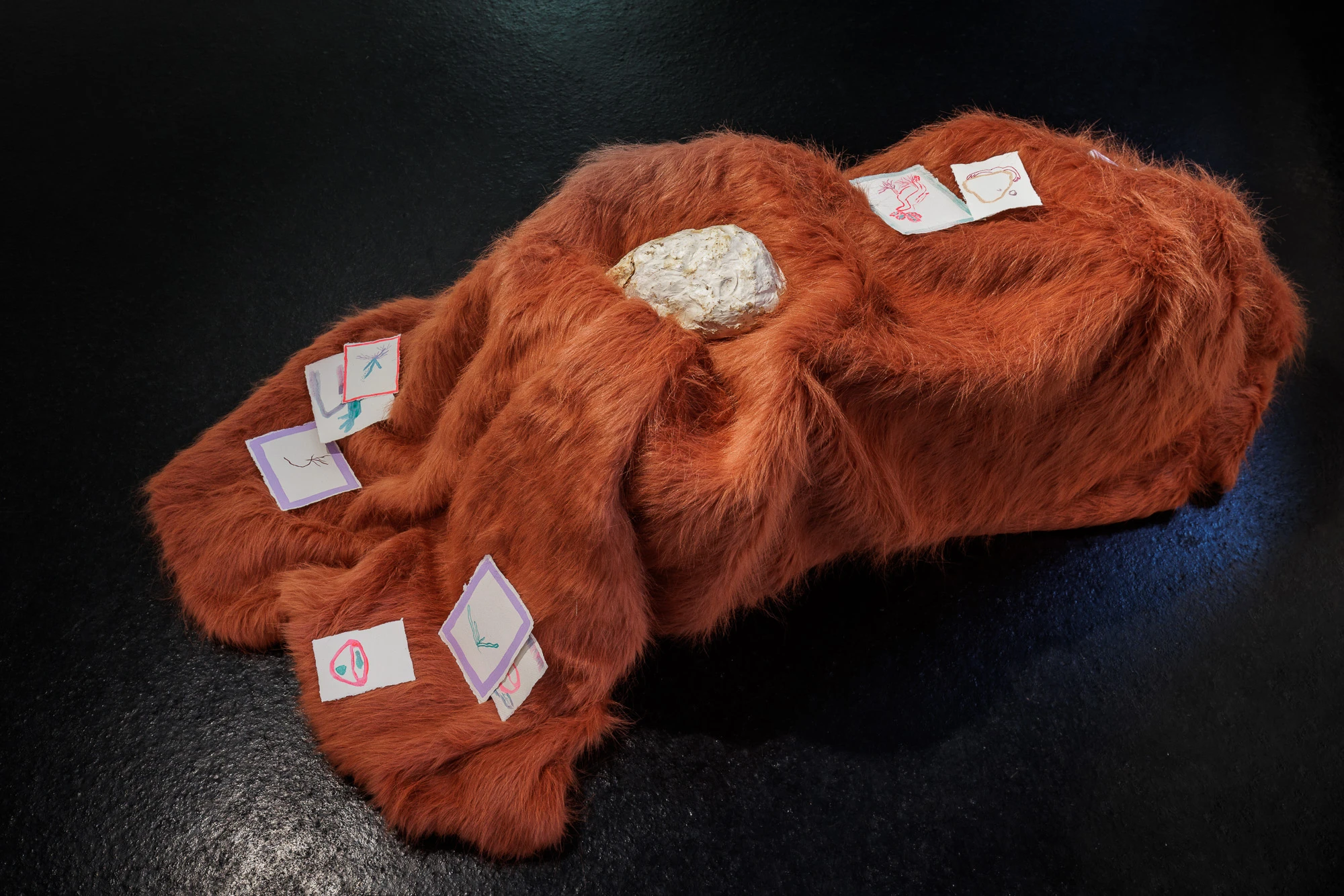

and moisture that is so essential for growing mushrooms.

The natural objects and others on the floor also oscillate between clear meanings and enigma: dried corn kernels symbolize the important plant that originated in Mexico; small mountains of woolen cord lie around; dried mushrooms; strips of Curcuma powder have to do with the Mexican tradition of healing and spiritual purification; copalresin used to purify bad energies; white sage for purifying any energies; volcanic pumice means ancestors in Mexico and is used for rituals; bamboo similar carizo sticks with synthetic fur symbolize power objects of the shamans, etc. The objects on the floor are usually laid on glittering papers in the colors of gold, silver, and copper to emphasize the meaning of the objects lying on them. Some gold papers have the shapes of leaves, which in Mexico were traditionally used as plates. Mirror effects that reflect light onto the walls are equally important to the artist alluding to the playfulness of natural light in landscapes like one that is reflected off of water and in this specific case to give the feeling of a dream or magic state. And on some sculptures, there are small cards with little drawings on them, like a mirror iteratively repeating elements of the canvases… This “magical dimension” is reinforced by the installations on the floor, which are more or less reminiscent of altars. Indeed as you enter Flores’ installation, the sense of cyclical time gradually prevails over linear time and you gently step from mundane everyday life into a sacred ceremonial world.

On a purple synthetic felt carpet that seems to float, there is a sculpture made of a filigree metal net and wood that rests on an sensitive balance: the artist thus interprets the harmony of nature, but also of mind and body, which can more or less easily be shaken. Somewhere you can find a fine fabric similar to that used in Mexico to collect the sea dew in order to capture its healing powers, trusting in nature. A small transparent Plexiglas cube out of which a mass of plaster is forced, hinting at the destruction of nature in an urban context. Thus, according to the artist, people in Mexican cities prefer the artificial and have largely forgotten the traditional knowledge of plants and nature.

Also the video “PARA SACARTE LOS AHUATES” (2023, To take out the Ahuetes) is embedded in this room, in which is the story of when Flores learned to clear pain with nature through the teachings of her grandfather. At the same time, it is the understanding and realization of what it means to be born and grow up in a place that is divided by socio-political circumstances, the border. That this division does not stop as a geopolitical division that only keeps people in check.

The relationship between natural and synthetic materials is remarkable. Paula Flores loves to mix natural materials with synthetic ones for her installations, such as glittering papers, skins, and felts. Some of them look very natural and thus imitate nature. And this is perhaps one of the essential feature that makes her work so appealing: the harmonic mixture of naturalness and artificiality, of clean, aseptic, almost digital elements of our contemporary world and natural, even archaic elements. And, on the level of form and content, this reflects scientific achievements and magical references, meaning and enigma, the willed and the arbitrary, waking consciousness and dream, which floods the entire installation.

In this context, a small but important element of the installation is to be deepened: the sculptures “MEDIATION” (2021) made from the mycelia of mushrooms.

Flores has been experimenting with mycelia for a long time to specifically grow them into compact shapes and then let them dry out, although in most cases this process also means the death of these living beings. The sculptures seem somehow like prehistoric eggs, which may have come from dinosaurs or are even of extraterrestrial origin. When you hold them, you notice how light and fragile these filaments that have grown together are. It is common knowledge that only the visible fruiting bodies are referred to mushrooms. However, the actual fungus is primarily the thin, thread-like structure (hyphae) of the mycelium in the soil or wood, which is usually not recognized due to its presence in these opaque substrates. Fungal mycelia can cover more than a square kilometer, have an enormous biological mass and reach a great age. Mycelia are crucial in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems due to their role in the decomposition of plant material and are the main factor in the health, nutrient uptake, growth and fitness of a plant. By bringing or forcing a hidden, essential living being so radically to light, so to speak, through her artwork, the artist intends to investigate and possibly rediscover and present what a fine, immense network of hidden correlations may exist. To achieve this goal duality must be overcome in favor of diversity. Without wanting to mystify physics, one can learn from general relativity that matter and energy, and space and time are densely intertwined and especially in quantum physics, phenomena occur that are (still) considered mysteries or even spooky. Anyway, the paradigm shift that has occurred from classical to quantum physics is finally beginning to take place in other natural sciences like biology and medicine. On the other hand there are also increasingly strong points of contact between the natural sciences and ancient indigenous knowledge such as in ethnobotany and ethnopharmacology – which Paula Flores also emphasizes in her research – as well as certain “scientific laws” that are reminiscent of “truths” that originate from meditative, mystical or even magical practices. It seems to me that the boundaries between the tangible and intangible are no longer so clearly defined.